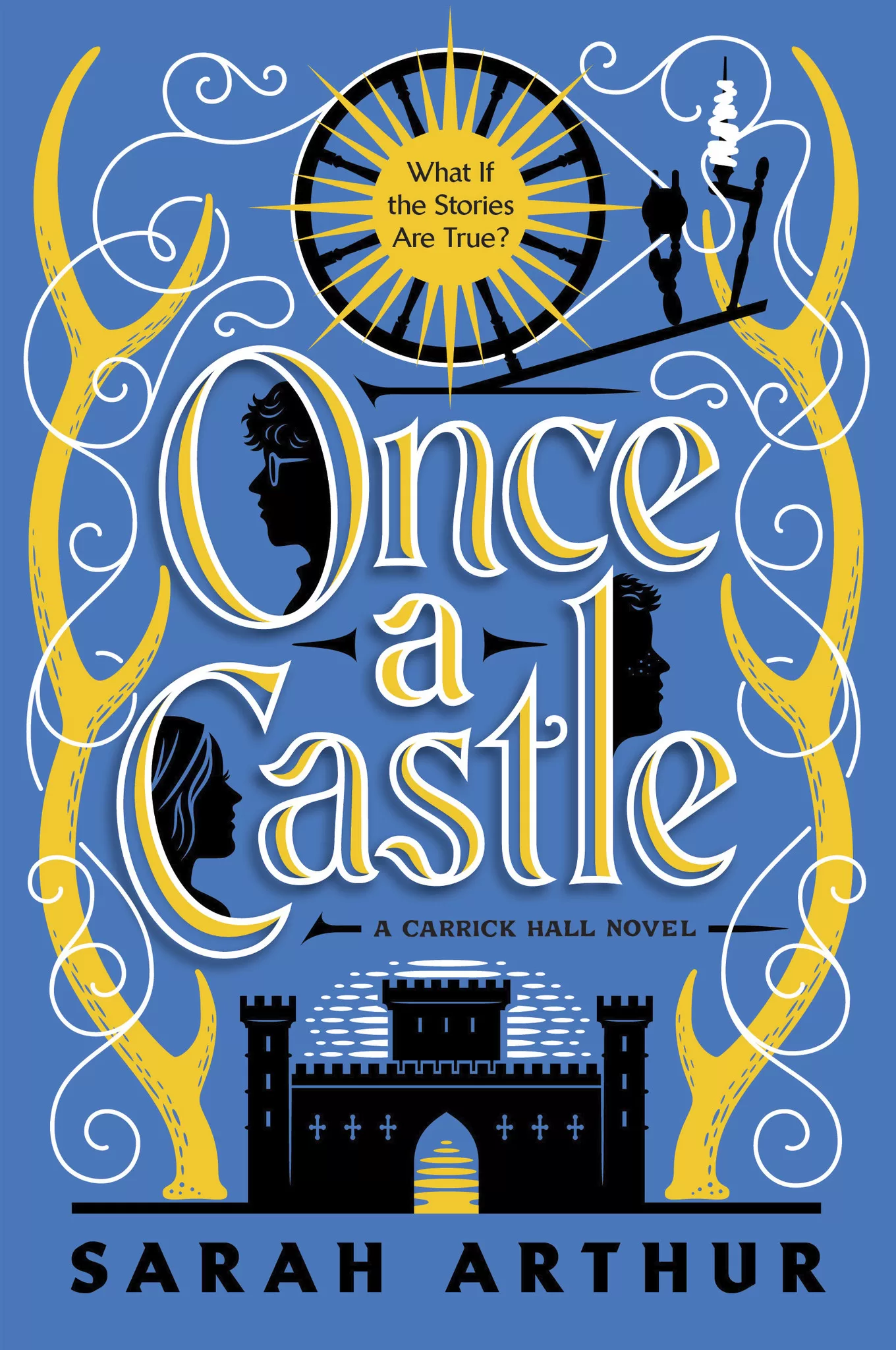

Hey, everybody! Welcome back to “Through a New Wardrobe”, where we sit down and chat with some of today’s hottest writers who have been influenced by CS Lewis and the Land of Narnia. For today’s interview we sit down for the long awaited second part of our interview with author Sarah Arthur . We are especially pleased to share with you an exclusive sneak peak and cover reveal for the second book in her Carrick Hall Series, Once a Castle. Enjoy!

NARNIAFANS: what Lewis said regarding his own conversion, of how he felt as though the “Hound of Heaven” were at his heels. Did the Francis Thompson poem that Lewis was alluding to inspire the story in any way?

Sarah Arthur: I’m aware of Thompson’s poem and its influence on Lewis, but if anything, my story is the other way around. When the stag first appears, you’ll note that he’s following Eva’s grandmother like “a protective rear guard” while Grandmother, in her dream-state, seems to be searching for something that eludes her. Later, when Eva meets the stag in the high mountains, he tells her, “Long have thy kindred hunted me,” and Eva replies, “Long have you evaded us, my lord.” So there’s this sense of longing, of pursuit, on the part of Eva’s family for something to fill the emptiness, the void that grief and trauma left behind. And the stag becomes the symbol for it.

NF: I’ll admit, at first I was caught up in the allure of Grandmother, yet as the story went on, it was hard not feeling like Grandmother was trying to fill some void in her life.

SA: Absolutely. This goes back to what I said about the stag. Eva’s grandmother may think that what she longs for is to be reunited with her lost loved ones, but that’s just a tiny glimpse of the glory and joy that awaits “in that far country.” And, in my story, only the stag can lead Grandmother there. But, of course, she blames him for her trauma; she fears and even loathes him. So the very thing she needs is the very thing she hates, which makes any sort of healing seem impossible. That’s the real tragedy.

NF: I thought the reveal when Eva discovered the pages and pages of newspaper articles about the railway accident was particularly well thought out. It never occurred to me that something like the rail way accident in The Last Battle would have been a major news story, at least at a local level. It brought to my mind the Kennedy Children after the death of JFK, Princes William and Harry after the death of Princess Diana, or even the “9/11 Children” and how those children became so closely linked to those tragedies. Even at her wedding Eva’s Grandmother was still called “The Tragic Beauty,” as if that was the sum total of her identity. In what way do you think growing up with that lingering spectre of her sister’s death would impact her attitude?

SA: Well, the rail crash was a real historical event that I discovered by accident more than twenty years ago. I was trying to figure out what on earth gave Lewis the idea to kill off a bunch of characters (in The Last Battle) in such a spectacularly disastrous way. I mean, why would his young readers have found that narrative device to be even remotely plausible? So I hunted around on the internet for possible railway accidents that might’ve taken place during the season in which Lewis would’ve been drafting the book. And sure enough: there it was. On Oct 8, 1952, three trains collided at Harrow and Wealdstone station in northwest London, killing 112 and wounding hundreds more: the worst rail crash in peacetime Britain. In fact, a memorial service for the 50th anniversary of the crash had just taken place at a church near the station, attended by survivors as well as by those who’d lost parents or siblings or other loved ones. Suddenly, what felt like the distant past or even a mere literary device became real. Actual people were still enduring the aftermath of the disaster, which had altered their entire lives. That discovery sparked the entire plot of Once a Queen.

Secondly, because the rail crash was a real event, there are all kinds of historical documents out there, including newspaper headlines, letters of condolence from the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth, from Churchill, etc. So I didn’t invent any of those. It was also the same era as the deadly London fogs, so the crash sparked lots of changes in railway safety. Anyway, back when I was first digging into the history (again, more than twenty years ago), there wasn’t a lot of info online about the rail crash. But since then, there’s been renewed interest in it, apparently, because you can find all kinds of stuff now, including actual film footage from the aftermath. It was absolutely horrific. If you were a survivor–or if you lost loved ones in such a huge national tragedy–it would shape your entire outlook forever.

NF: I won’t lie, of the characters, I think I felt the most sympathy for Gwen [Eva’s mother]. In many ways it felt like she was caught trying to keep the peace between her mother and daughter based on her own childhood. My heart really broke for Gwen when she told Eva that Grandmother didn’t approve of Gwen marrying Eva’s father, and even implied he didn’t love her and was only using her to advance his career. We talk a great deal about physical and mental trauma that can endure after a major event, like the rail way accident, but hurtful words like that can be just as painful. How might this affect Gwen, not only in terms of her relationship with her mother, but with her husband and Eva?

SA: I think it’s pretty telling that the book opens with Eva’s first time ever meeting her grandmother–and yet Eva is fourteen years old. That’s a long time to go without meeting someone significant in your extended family–even if they do live an ocean away. Clearly there’s some deep wound that Eva’s mum bears. Gwen has had to create very clear boundaries to protect her own emotional and psychological wellbeing after such an enormous relational rift. But we also get the sense that Grandmother had always kept her distance from Gwen, shielding her own self from further hurt (Grandmother had already lost a bunch of loved ones, after all, and parenthood is nothing if not a series of losses). But grownups can’t do that to children. We can’t protect ourselves in ways that damage the young ones in our care. Which eventually Gwen realizes in her own relationship with Eva. It’s a wicked cycle that plays out in far too many families, and Gwen decides to disrupt it, even if it means risking getting hurt all over again.

JS5: Gwen tells Eva that she didn’t share with her the news about the railway accident because her daughter possessed a very vivid imagination and would be troubled by nightmares. I was reminded of the approach my own parents had with me and my younger sisters regarding “earth shattering events” for that very reason, and I’ve noticed for my own nieces and nephews that children in general, do tend to have very strong imaginations. When I look back on my own childhood, I was 10 when the Oklahoma City Bombing happened and in high school when the 9/11 attacks occurred. Back then, “taking a break” from the bad news was as easy as changing the channel. Now, however, that kind of news is almost everywhere with social media and smartphones and the internet. What role, if any, do you think parents, like Gwen have in helping their children navigate those kinds of moments?

SA: It’s a tricky thing, because, on the one hand, we can’t shelter our children so much that they’re unable to function in the “real” world. But on the other hand, we must be aware of what’s developmentally appropriate for them to handle, in addition to getting a solid grasp on each child’s unique temperament. What’s terrifying to one kid might not bother another kid at all. (Not every child has a vivid imagination, actually. Some of them are able to maintain an almost scientific detachment and inquisitiveness.) But in Eva’s case, Gwen understood Eva’s temperament as overly imaginative. In time, I think Gwen realized she couldn’t use that as an excuse to avoid dredging up the pain of her own past, because that wasn’t fair to Eva.

Incidentally, it’s worth noting that the ability to shelter children from harm is a form of privilege. Many parents around the world are unable to do so because of inherently harmful environments over which they have little-to-no control, whether due to economics or war or oppression or any number of inescapable realities. To grow up in a setting where you’re allowed to mature at a healthy pace is extraordinarily rare in the history of humanity. I don’t want to ever take that for granted.

NF: Absolutely. You mentioned in the Afterword that Eva’s experiences were inspired by your own when your grandmother was suffering from cancer. Was there anyone in your life who played a similar role as a buffer to help you through it?

SA: I don’t know if “buffer” is the right word. But my parents were certainly fully engaged, not only in taking care of my “Oma” (which is what we called her), but in helping me–as a fourteen-year-old girl– process the experience.

Some of it was by example. For instance, I remember passing by the bathroom where my mom had set up a plastic chair in the tub so she could wash Oma’s hair. Oma was on a lot of meds, by that point, and I clearly remember hearing her saying, in a childlike voice, ”I’m being a good girl, aren’t I?” And she wasn’t being silly, either: I could hear the anxiety in her tone. I’ll never forget my mom’s reply: “Yes, of course, Mom: You’re a very good girl.” The pathos of it was heartbreaking. But my mom’s compassion was incredibly powerful. It taught me that we must show up and love people even when it’s hard.

At other times, my dad, who is now a retired Presbyterian minister, helped me process the theological implications of Oma’s decline and death. I remember asking him what would happen when Oma died. I knew she didn’t profess to believe in God–that she was probably, on some subconscious level, really angry with God–and it made me worried that death would be the end, that I’d never see her again. My dad, who is a kind, gentle man, said something like, “Well, we don’t know what will happen. We’re not God. And we’re probably going to make mistakes in how we think about it all. But if we err in any direction, let’s err on the side of grace.” I’ve never forgotten that.

NF: Wow. That’s powerful.

NF: I geeked out at some of the Lewis references, namely the gardener named “Paxford”, “Barfield Circle” in reference to Owen Barfield, and of course the groundskeeper’s family having the surname Addison after “Addison’s Walk” the park at Oxford where Tolkien and Lewis had many conversations about God and literature. Were there any I missed? Any you’re saving for later books?

SA: I had a blast leaving “Easter eggs” for readers! If you know even a little bit about Lewis and his colleagues and family, you’ll find more and more references every time you read through the series.

For instance, as you noted–even though my character is named “Paxton” (not Paxford, like the Lewis brothers’ employee) and he’s the chauffeur, not the gardener–I was definitely thinking of the historical Paxford, particularly since some scholars believe he was Lewis’s inspiration for the character of Puddleglum in The Silver Chair. And yes, the Addison family in my books is named for Addison’s Walk–but also, if you look up that surname, it means “son of Adam.” In fact, almost every name and location in my books was chosen on purpose to evoke some memory or reference for my readers. Not the least of which is Jack Addison, the middle sibling, who becomes one of the main characters in book 2 of the Carrick Hall novels, Once a Castle (releasing Feb 11, 2025). I encourage you to find more!

NF: Absolutely. And to that end, our loyal fans, and friends of Narnia, I am pleased to share with you all our exclusive cover reveal for book 2, Once a Castle, as well as link to a sneak speak at the novel here. Preorder your copy today.